This article is a critical analysis of the game Papers, Please.

I will

discuss Core Mechanics,

diagram the Core Loop, and

describe the Minimum Viable Product (MVP). If I were to make this game, how I would prove in the physical, paper or digital format.

Core Mechanics

• Rulebook and newspapers: Reading news articles and daily rules.

• Stamping passports and papers: Denying or approving entrants’ passports.

• Managing money: Spending savings and salaries on rent, food, heat, medicine, and booth updates. Salary depends on how many entrants are inspected within the time constraint.

• Speaker: Calling “NEXT”.

• Clock: Calling it a day when time runs out.

Core Loop

Minimum Viable Product

This minimum viable product (MVP) needs the following features to prove the concept:

• Rules for denying and approving.

• A timer (signal) that indicates the beginning and end of a day’s work.

• Alternatives of entrants, their passports and papers.

• Count how many passports are processed correctly.

• Calculate the salary after work.

• Income and expenditure list.

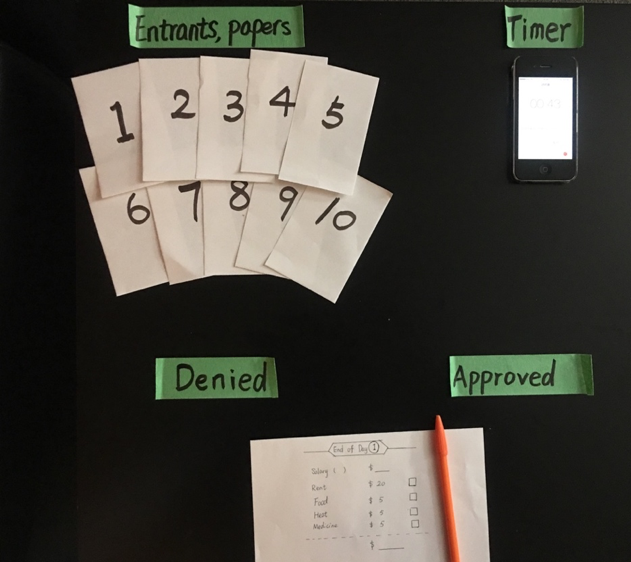

The MVP scenario (Figure 1) reflects the core mechanics and core loop of Papers Please. The table represents booth of the immigration officer, and ten cards with the numbers “1” to “10” represent 10 entrants to be inspected. Before the game begins, rules (rulebook) are verbally explained to the player by the organizer (me): Within one minute, the player should deny cards with an odd number, approve those with an even number, and take one card at a time. The cards are put on the top left hand side of the table, which correspond to entrants waiting area; a phone displaying a timer is on the top right hand side of the table, which represents the clock in the immigration officer’s booth; the bottom left and right areas of the table represent the denied and approved entrants respectively, which represent the entrants who have had their passport stamped “denied” or “approved”.

Once the timer starts, the player needs to take cards one by one from the upper left hand zone of the table, and classifies them as either “denied” or “approved” by placing the card on the respective areas of the table. When the timer rings, the player stops moving all cards. I check the number of cards the player has correctly classified (Figure 2), count their salary, and write down the amount of money they have earned on a sheet of paper. Each correctly classified card earns them $5. A piece of paper, with the player’s personal income and daily expenditures, is then handed to the player and they are asked to check which items they would like to purchase (Figure 3). The day ends when the player chooses the items they wish to purchase.

© Wenyi Gong 2018

Comments